Employees working in United States companies spend approximately 2.8 hours each week involved in conflict.

This is about $359 billion in hours paid that are filled with/focused on conflict instead of on productivity. This equals 385 million days on the job going toward conflict, as opposed to being put toward collaboration. This is a full day of productivity each month and 2.5 weeks of productivity each year. (CPP Inc., 2008).

Despite these numbers, it is important to know that not all conflict in the workplace is bad.

At some point in our professional lives, we have had a conflict with a peer, leader, direct report, etc. In a recent article for Fast Company, Dr. Tracy Brower discusses how conflict has its benefits and how the key is knowing how to handle it effectively.

To better understand your emotions and what specifically may be triggering your response to conflict, she notes the importance of being personally aware and reflecting on your reactions. Then, she describes how one must be intentional in choosing their own path to manage conflict successfully.

“Dialogue is the most effective way of resolving conflict.”

Tenzin Gyatso

The 14th Dalai Lama

It caused me to reflect on how my own conflict style has changed over the years, learned through the Thomas-Kilman Conflict Mode Instrument, which assesses an individual’s behavior in conflict situations.

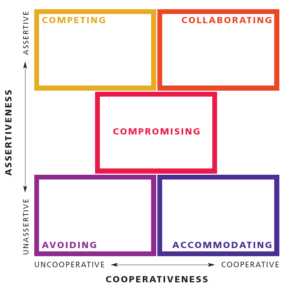

The assessment describes a person’s behavior along two dimensions:

- Assertiveness: how someone tries to satisfy their own concerns, and

- Cooperativeness: how someone tries to satisfy another person’s concerns.

These two dimensions define five methods of dealing with conflict:

- Competing is assertive and uncooperative, a power-oriented mode. When competing, one pursues their own concerns at another person’s expense, using whatever power seems appropriate to win their position. Competing might mean standing up for your rights, defending a position you believe is correct, or simply trying to win.

- Collaborating is both assertive and cooperative. When collaborating, one tries to work with the other person to find a solution that satisfies both people. It involves digging into an issue to identify the underlying concerns and finding an alternative that meets both sets of concerns. Collaborating between two people might take the form of exploring a disagreement to learn from each other’s insights, resolving some condition that would otherwise have them competing for resources, or confronting and trying to find a creative solution to an interpersonal problem.

- Compromising is intermediate in both assertiveness and cooperativeness. When compromising, one has the goal of finding a practical, mutually acceptable solution that partially satisfies both parties. Compromising falls on a middle ground between competing and accommodating, giving up more than competing but less than accommodating. Likewise, it addresses an issue more directly than avoiding but doesn’t explore it in as much depth as collaborating. Compromising might mean splitting the difference, exchanging concessions, or seeking a quick middle-ground position.

- Avoiding is unassertive and uncooperative. When avoiding, one does not immediately pursue their own concerns or those of another person. They do not address the conflict. Avoiding might take the form of diplomatically sidestepping an issue, postponing an issue until a better time, or simply withdrawing from a threatening situation.

- Accommodating is unassertive and cooperative – the opposite of competing. When accommodating, one neglects their own concerns to satisfy the concerns of another person. There is an element of self-sacrifice in this mode. Accommodating might take the form of selfless generosity or charity, obeying another person’s order when you would prefer not to, or yielding to another’s point of view.

In 2018, my predominant style was Avoiding and the reasoning was spot on. Avoiders see conflicts as intrusions or disruptions that divert energy from work and cause unnecessary stress. In short, conflicts were a waste of my time, as I would have rather addressed only important issues and only when the conditions were right.

In early 2021, my predominant style became Competing. Competitors tend to see conflicts as contests between opposing positions and the people who hold them. Believing in their position, they try to win these contests. Examples of situations where this style is useful are when decisive action is vital (i.e. in an emergency) or on important issues when unpopular courses of action need implementation (i.e. terminations). Coming off the year I had in 2020, where timely and decisive actions were needed in crisis and I implemented a few unpopular decisions, I fully understood how and why my styles shifted. Further, I was also trying to progress my career around this time, so I was very intentional in other processes in which I was involved, as I wanted to “win.”

What I learned was that, in the case of conflict-handling behavior, there are no right or wrong answers. All the methods mentioned above are useful in the appropriate situations and should be done respectfully. And as Dr. Brower aptly notes in her closing, “… a deep respect for others and for their rights to differences of opinion are core to cultures in which everyone can learn, grow, and feel part of a respectful community.”

I am fortunate to be a part of such a community.

- How familiar are you with your own conflict style?

- How do you handle conflict when working as part of a team?

- How does your organization’s culture react to conflict?

Please feel free to share your thoughts in the comments.

Be well,

Brian

—

Brian Aquart is the Creator and Host of the Why I Left Podcast, a show chronicling real stories from real people about why they left their jobs during the pandemic. Stay up to date with Brian on LinkedIn.